At the age of 96 serves as a LightHouse for Generation-Next

by Ravi Kant Bhatanagar

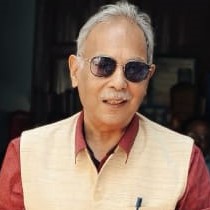

Ved Prakash Vatuk, a sole warrior, a loner, fighting for India’s rich heritage, her plural society, and engaged in promoting Hindi, as the voice of our nascent democracy and a nation, during his active years, travelled worldwide, quietly completes 96th spring of his life on the auspicious Vaisakhi Day, 13, April, this year in Meerut, which had faced genocide after the 1857 uprising against the unrestricted loot of a British business house, East India Company.

There was no hustle-bustle in the city of Meerut, a historical city from the Mahabharata times, no shouting of the muscle-flexing security men or the police sirens creating a passage in the busy streets or lanes indicating any movement of the men in power, often witnessed, when men in power decide to honour a well-known legend or a celebrity.

The quiet birthday celebrations in this revolutionary town of Mangal Pandey, who had ignited the spirit of freedom in 1857, however, has reaffirmed the

growing chasm between the today’s rulers and the eminent persons of our society engaged in reasserting India’s ‘tryst with destiny’. Pandit Nehru’s historical speech always inspires and even haunts people like us, who were educated and groomed in the much-revered academic environs of the Allahabad University. Allahabad, now renamed Prayag, was the hometown of Jawaharlal Nehru, Mahadevi Verma, Sumitra Nandan Pant and also Urdu poet, Firaq Gorkhpuri, and this author’s close bond with the city could not be diluted despite my long innings in the service. Therefore, it was natural for people like us to be bonded with the creativity of Meerut, where I have decided to live after my superannuation.

For this author joining Vatuk’s birthday, perhaps, could be reinventing the unforgettable past of the Allahabad town, which has not only been the confluence of the holy rivers, Ganga, Yamuna and Saraswati, it was also the centre of the country’s political and literary movements. The presence of young writers such as Eeshwar Chand, Satyapal Satyam, Bhagwan Dikshit, Sabhir Choudhary, and Ghanshyam Das Verma and many other prominent people at the birthday celebrations was like the rekindling of the Meerut spirit for revolution.

With the rest of his family opting to live in the US, Vatuk lives all alone, looks after himself, uses magnifying glasses to continue his writings, a task he had begun when he was just 19. Later, this soldier of pen travelled across the continents to foist India’s intellectual flag. His first essay had appeared in the Sunday supplement of the Navabharat Times, a Times of India publication, during the golden era of Indian journalism under the leadership of Rama Jain, who had also initiated the publications of the famous Hindi weeklies such as Dhrmayug and Dinaman. These publications could be compared with the top magazines in the West, however, her scions, Sameer and Vineet, dwarfed intellectually by getting some management education in the US, not only closed down the Hindi magazines, but also converted the classical Hindi used in the Navabharat Times to Hinglish.

Vatuk, however, had embarked upon his solo mission with an advanced degree in Hindi from the Punjab University, and did post-graduation in Sanskrit from Agra University in 1954. A few months later, he began his voyage to England to work for his Ph.D. dissertation at London University. In 1959. Vatuk migrated to the US, where he served as the director of the Berkeley Institute of Folklore in America. His two books, the Diary of Baba Hari Singh Usman, one of the founders of the Gadar Party, and Uttar Ram Katha, have received international attention.

Kiara Hall’s tribute enabled the scholars across the world to describe him as an influential poet and activist, reflecting on his life, work, and impact on social justice. She had presented a document at the launch of the “Studies in Inequality and Justice: Essays in Honour of Ved Prakash Vatuk”. In this document presented at the University of California at Berkeley, she has offered an insight in the context of Vatuk’s unique contribution in highlighting the anguish and challenges on the South Asian regions, his activism against the practice of hiring practices in academia and his role in fostering inclusive dialogues in the field. The tribute also underscores Vatuk’s lasting legacy in promoting human rights and addressing social inequality, as well as the connections fostered among scholars through his work.

(Author has post-graduated in economics and also earned a Ph.D., served the government as a commissioner. He is the general secretary of the Goodwill Society)