An Uncompromising Journalist like a Prince and a Legend among Editors

Among his contemporary peers, he was a loner, when Hari Jaisingh was picked up by India’s irrepressible newspaper magnet, Ramnath Goenka, to edit the Indian Express published from Ahmedabad. Little did he realize that he is grooming a journalist, who might refuse to make any compromise for surviving in the coveted post of an editor? It was quite surprising, when in eighties; he joined National Herald as its editor.

Many may ask why he enjoyed so much respect in almost every section of the society, the answer is simple, and he had never harbored any ill-will or vengeance for anyone. His writings were always judicious. In personal life, while some of his peers own farm houses in Delhi’s elite areas, he took bank loans to ensure higher education for his children. It may be recalled that once Delhi’s chief minister told this author that why Haribhai did not ask for any favors from the politicians, whether seeking a plot at Panchkula in Haryana or a farm land in Delhi. He even mentioned the names of some of his peers and successors, who were able to get big bungalows in South Delhi and even a farm house. The answer, perhaps, could have been we exercise our choices.

During early years of his presence in the national media platforms, especially in eighties and nineties, perhaps, being divided among different ideological groups was not taken seriously. He did not represent any ideology or political outfit, but his journalism was just an emphasis on the truth.

It is yet to be explained that why did he accept a sick publication, which perhaps was already abandoned by the then Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi. Interestingly, she had given the management to Yashpal Kapoor, known for doing India Gandhi’s dirty political maneuverings. Earlier, Indira Gandhi had evicted M. Chelapati Rao, one of the most admired journalists during decades of sixties and seventies, by force. He was pushed from his chair at the Herald House, Bahadur Shah Zafar Marge, New Delhi, perhaps, by Yashpal Kapoor, either himself or by his goons. A few weeks later, Chelpati Rao was found dead at a tea stall in the Pandara Park, near India Gate. He never revealed, but according to the Congress Party sources, he was lured to accept the challenging task by a union minister known for his proximity to India Gandhi and Kapoor.

Since National Herald was one of the most admired dailies before India’s freedom struggle, this author also joined the daily a few months later after Hari Jaisingh. One year later, however, I had to quit due to some professional as well as other reasons, and Haribhai too resigned, but Goenka asked him to rejoin your old assignment in Ahmedabad. During this period, the Times of India offered him the position of editor at its proposed Bangalore edition; he however, declined the offer, later he became Editor-in Chief of the Tribune at Chandigarh, where he led the editorial team for next nine years.

The Tribune Years– Hari Jaisingh’s commitment to the truth became a countrywide mantra during his tenurein The Tribune, when his page one editorial boldly pursued the truth. Even today, it is considered a milestone in the Indian journalism. Later, he commented that “There has been an overwhelming response from the people to the front-page editorial “No, My Lord!” (The Sunday Tribune, May 5, 2002). I never thought that ideas or ideals like the people’s right to information, freedom of the Press and transparency in the investigation process of the PPSC scam would evoke such massive support from the readers.

“The huge number of telephone calls since then gave me a clear indication of the citizens’ perspective on the most sensitive arm of governance symbolised by the judiciary” he further stated.

His conclusion are quite illuminating even after 23 years that, one, the people are alert and alive to the goings-on in the polity though they generally prefer to remain silent. However, once they feel that they are getting the right lead on matters dear to their hearts; they do not hesitate to speak out. Two, in addition to the general disgust at the existing state of affairs, the people seem to be nursing bottled-up feelings even against the working of the judiciary. They resent certain functional aspects of the judicial system, the general drift and the growing shadow of undesirable activities. The sharp public reaction was a revelation. This may come as a shock to all those who have put the judiciary on a high pedestal, and rightly so. The people have had high expectations from the judges. They do not want them to be part of the aberrations that the rest of society suffers from.

Three, once convinced about the correctness of the cause, the people are willing to go along with the bold and the upright. The spontaneous response of thousands of lawyers in Chandigarh and other parts to the issues of freedom of information and corruption is unprecedented. It is a landmark event. This should help us to keep our hopes alive for a better system and better times ahead.

It cannot be overemphasised that the people have not taken kindly to the affairs in the Punjab Public Service Commission. They are terribly angry at the trading in jobs. The judiciary needs to bear in mind the public sensitivity in the matter while looking at legal tangles in the Ravi Sidhu case. What is right and what is wrong can be interpreted differently in legal terms. All the same, everything needs to be viewed in the larger framework of how public institutions and persons at the helm should conduct themselves. Truth has to be seen as truth. It cannot be turned into falsehood with the help of legal jargon.

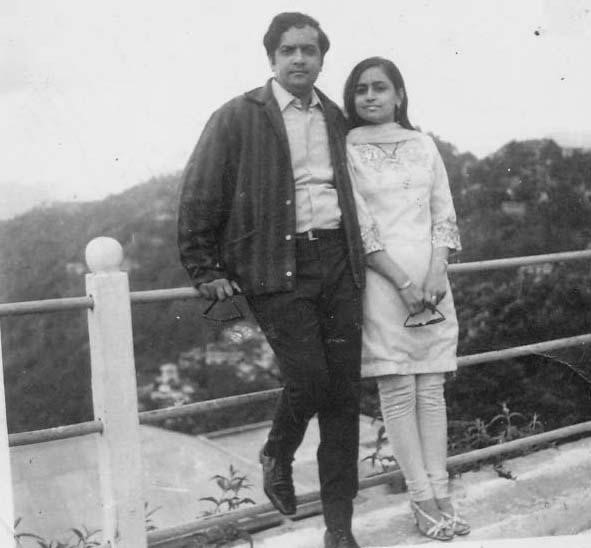

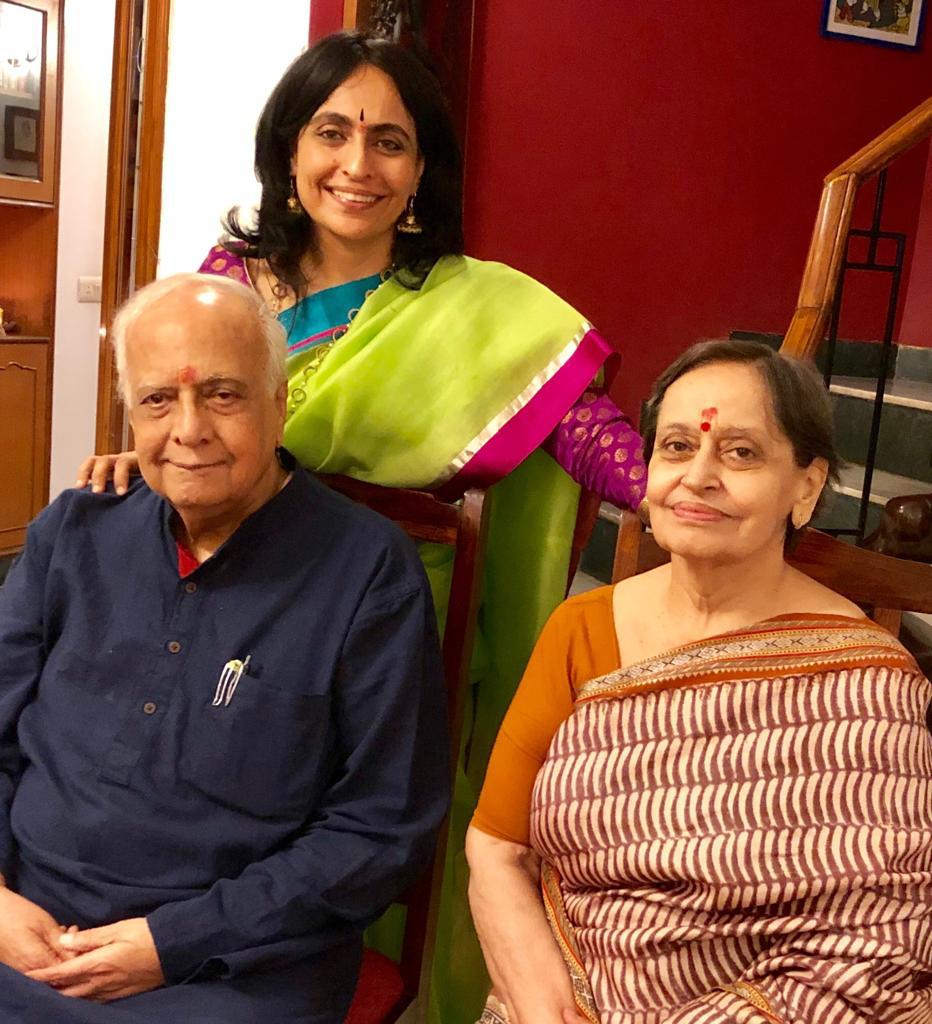

The Lamp Post– Few among journalists know that his grandparents had migrated from Karachi to Kolkata, where he had received education. During the past five decades, he had been serving in a number of newspapers, but he also brought in an aroma of Bengal, where he received education. His innings in Gujarat inculcated in him objectivity and the prolonged stay in Chandigarh, enabled him to be reinvigorated by the dynamism of Punjab.

In 2017, he, perhaps, was quite happy, when the president of the Tribune Trust was summarily sacked for apologising to a drug peddler. He once informally stated that like any other profession, journalism may be undergoing difficult periods, but its energy is alive.

On April 1, he suffered brain stroke and had remained hospitalised till April 23, when he breathed his last. He was a sticker for professional ethics and embodied rich human values; he was a good human being. He did not communicate his last wishes to anyone, but his deeds will continue to illuminate us, stated Ashwini Bhatnagar, a noted author, who had served in the Tribune as his close associate.