*Aruna Bhattacharya believes early diagnosis and accessible treatment can transform India’s TB woes

Every day, 3,500 people worldwide lose their lives to tuberculosis (TB), and around 30,000 people become infected with TB bacilli, according to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates. India alone accounts for 27% of global TB cases. This is jarring, given that TB is a detectable and curable disease and TB diagnosis and treatment protocols have been a part of existing health systems for a long time.

World TB Day, on March 24, commemorates Dr. Robert Koch’s discovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (the bacteria that causes tuberculosis) in 1882. Despite its discovery then, possible treatments using streptomycin in 1943 and the discovery of antibiotics such as isoniazid and rifampicin in the 1950s and 1960s, the war against the pathogen is far from been won, and there are multiple challenges to be overcome in combating the disease.

India remains a TB hotspot. The TB control programme in India has undergone several changes since its inception in 1962, incorporating evidence from various domains of public health and health systems, including pharmacology, microbiology, epidemiology, the social sciences, and information technology.

The theme for World TB Day 2024 (March 24), ‘Yes! We can end TB!’, underscores the potential to eradicate TB with existing disease control mechanisms, infrastructure, training, and the political will. Yet, TB in its various avatars — drug-resistant (DR-TB), totally drug-resistant (TDR-TB), extensively drug-resistant (XDR-TB), pulmonary TB (P-TB) and non-pulmonary TB — seep out, akin to trying to hold sand in one’s hand, only to have it slip through one’s fingers.

We are in an era of hope where public health discourse has gained importance and technology has narrowed the gaps that were previously unimaginable. The COVID-19 pandemic, despite its disruptive and uncertain nature, has brought to the fore preventive aspects of public health, highlighting social determinants of health in the scheme of things. Despite the passage of World TB Day 2024, looking at rapid urbanisation, migration, and the stresses on the existing health systems, I propose a 10-point agenda towards ‘ending TB’.

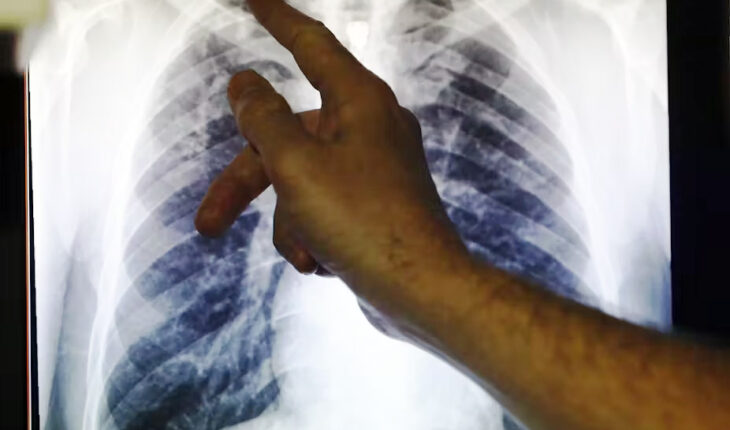

First, early detection. Given TB’s aetiology, early detection is the key. Symptoms are often ignored and mistaken for other common ailments, leading to delays in reporting. Compulsory screening for family and contacts of each index case is essential, necessitating availability of laboratory facilities and efficient follow-up mechanisms within health systems.

Second, precise treatment categorisation. With increasing DR-TB, it is imperative to know the resistance status at the time of diagnosis to assign appropriate treatment regimens as per their phenotypic susceptibility.

Third, treatment adherence and follow-up. Unlike other bacterial diseases, TB requires a long period of sustained treatment. Often, this leads to non-compliance, which could be due to observable improvement in health status, or change of residence, movement across States and districts. Even though the TB control programme has a built-in follow-up system, compliance to complete treatment is not 100%. Leveraging technology to monitor compliance needs focus.

Fourth, zero mortality. Mitigating mortality due to TB, be it DR-TB or non-pulmonary TB, is necessary.

Issue of drug resistance

Fifth, controlling drug resistance. Drug resistance in TB remains a man-made phenomenon. Unregulated use of antibiotics and non-compliance with treatment regimens lead to selective evolutionary pressure on the bacillus, in turn resulting in developing drug resistance. Poor regulatory mechanisms for drug control and non-compliance with treatment regimens are the main reasons for such a high degree of drug resistance.

Sixth, assessing the extent of drug-resistant TB. There needs to be data on the proportion of people diagnosed with TB who have rifampicin-resistant TB (RR-TB) and multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) — this is resistance to both rifampicin and isoniazid, collectively referred to as MDR/RR-TB. This helps in better plan and design of the control programme, resource allocation for diagnosis, the treatment regime as well as availability of trained staff mandated for DR-TB.

Seventh, availability of appropriate medicines. Assured medical supply is mandated under the TB control programme. However, procurement challenges for DR-TB medications such as bedaquiline and delamanid must be addressed, in addition to ascertaining treatment facilities for all DR-TB cases which require in-patient care.

Integration of intra-systems

Eighth, integration into larger health systems. Strengthening referral networks within and between different levels of public health systems and private health systems is vital to ensure no symptomatic cases are lost, no patients miss their dosages and are non-compliant, and, importantly, the screening of contacts for all positive cases of pulmonary TB cases (DR or non-DR).

Ninth, dynamic notification system. A robust notification system will ease the burden of health system personnel. While Ni-kshay has evolved — ‘Ni-Kshay-(Ni=End, Kshay=TB) is the web enabled patient management system for TB control under the National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme (NTEP)’ — it requires improvements to capture real-time TB data between sectors, practitioners, time, and locations.

Tenth, considering population mobility and migration. Often, the productive aspects of life are overlooked when discussing disease and health care seeking, particularly in the context of TB, which suffers from social and cultural stigma. Interestingly, once TB is diagnosed and positive cases are put on treatment, health is restored quickly for the patient to resume their daily activities. Therefore, portability of TB treatment within the country is crucial at the policy level. Let us pledge to create a TB-free India and world. With early diagnosis and continuous treatment accessible to all, we can achieve the goal of ‘Yes! We have ended TB!’

Aruna Bhattacharya is Lead – Academics and Research, School of Human Development, Indian Institute for Human Settlements. She is a medical anthropologist and public health specialist with over two decades of experience of working on tuberculosis control. Views are personal.